Estimated reading time: 9 mins

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a debilitating condition that is otherwise known as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). Due to the diverse set of seemingly unrelated symptoms that people with this condition present with, it is commonly misdiagnosed and can often be confused with other conditions such as depression.

Typical symptoms of CFS can be:

- Sleep problems

- Muscle and joint pain

- Headaches

- Memory and concentration problems

- Flu-like symptoms

- Feeling dizzy or nauseous

- Low mood

A mysterious illness

CFS has long been stigmatised and ignored by many doctors due to its mysterious aetiology, often leaving many physicians baffled. This has commonly led to doctors concluding that it is purely a psychiatric illness, rather than a disease of some kind. Sadly, this means that many patients go through years of seeing various doctors before they get a proper diagnosis.

According to the National Institutes of Health, CFS impacts 15 million to 30 million people worldwide, and leaves 75% of those affected unable to work and 25% homebound or bedridden. Although the aetiology of CFS is unclear, the condition commonly arises following a viral illness, in particular Epstein-Barr virus, herpes and mononucleosis. Since the coronavirus outbreak, there has been a large number of reports of people suffering with long-term symptoms that are akin to those of CFS. This has led to a new line of research opening, to examine the biochemical mechanisms that are leading to symptoms, such as debilitating fatigue, low mood and brain fog, headaches and more in those who have been infected with COVID-19.

A new angle to understanding COVID-19?

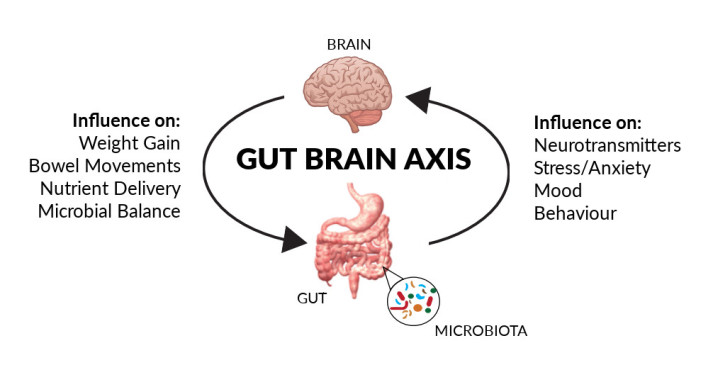

According to a report1 published by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, more than a third of those who have tested positive for COVID-19 and have symptoms don’t feel like they’re fully recovered, even weeks and months later. Why might this be occurring at such alarming rates? Some researchers, such as Mady Hornig, Immunologist at Colombia University, have proposed that this may be due to inflammation levels going haywire in the body. COVID-19 patients exhibit abnormally high levels of inflammatory molecules2, such as certain cytokines like interferon gamma, which are coincidentally the same inflammation driving molecules that are chronically present in CFS patients. This overactivation of the immune system, which has frequently been labelled the ‘cytokine storm’ in the acute phase of COVID-19, may be what is leading to long-term problems.

Neurovirologists such as Avindra Nath, at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, believe that there should be more attention placed on the long term risks of COVID-19. Nath purported, in an article published in The Scientist, that viruses can seek long-term refuge in organs to hide from the immune system, which can essentially cause a constant trickling of virus particles to escape into the bloodstream leading to a chronic trigger of inflammation. However, the most obvious mechanism by which viruses can cause symptoms related to CFS is autoimmunity. Nath explains how during the acute phase of a viral infection, the body’s immune system can mistake its own proteins with viral proteins, due to an overactivation of inflammation. This, over time, can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction

A defect in the batteries of our cells?

The mitochondria are the battery-like organelles of our cells, which play an important role in a wide range of physiological processes, such as creating APT (the energy currency of our body), as well as neurotransmitter synthesis, production of insulin, iron metabolism, heat production and many more. Damage to the mitochondria can therefore have a global effect on the body, and many chronic diseases such as diabetes, psychiatric conditions and heart disease, are related to poor mitochondrial function. A key example is in the lack of ATP production that can occur in mitochondrial dysfunction – without enough ATP, we begin to experience symptoms of overall malaise, exhaustion, muscle pain, brain fog and low mood. A chronic inflammatory response that can be triggered by acute viral infections, can literally wear down the mitochondria, altering the metabolism and functioning of cells. This can have a far-reaching impact on our body and even lead to problems in normal bodily functions such as sleep.

An example of this was seen in a case-controlled study3 carried out in 2011 and published in BMC Neurology, which looked at 22 healthcare workers who had been infected in 2003 with SARS-CoV-1 and were left with chronic exhaustion, musculoskeletal pain and sleep disturbances. After performing EEGs (electroencephalogram) on the study participants, they found elevated levels of alpha EEG anomaly and apnea. The alpha-EEG anomaly has been found to interrupt normal restorative aspects of sleep and many studies4 have identified this anomaly as a consistent feature in patients with fibromyalgia, a condition that leads to similar symptoms to CFS.

The best offence is a good defence

As the well-known adage goes, ‘the best offence is a good defence’ – the most important thing we can do to protect ourselves from the negative impact of viral infections like COVID-19, as well as prevent potential long term effects, is to optimise our health via nutrition and lifestyle approaches. A key trigger for mitochondrial impairment is oxidative stress5, caused by the following factors:

- High blood sugar levels/insulin resistance

- Consumption of inflammatory foods

- Chronic stress

- Alcohol

- Cigarette smoking

Oxidative stress is a term used to describe the impact that reactive oxygen species (ROS) can have on our health, which are chemically reactive unstable molecules that contain oxygen. These molecules scavenge electrons from other molecules, leaving a trail of disruption called free radical damage. It is well known that under normal conditions, our bodies maintain a healthy balance between ROS and antioxidants, which are molecules that can donate electrons without becoming ‘unstable’ themselves and are therefore able to halt free radical damage.

Having chronically high blood sugar levels, drinking too much alcohol, smoking, eating too many processed foods and chronic stress, are a recipe for free radical damage and therefore mitochondrial dysfunction. Here are some simple dietary changes to prevent this from happening:

- Avoid sugar, in all its forms

Sugar can come in many forms, which is why it’s important to read ingredient labels. Food manufacturers often try to sneak sugar in by using other types of sweeteners such as dextrose, maltodextrin, syrups, fructose, sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, agave, fruit concentrates and honey. Avoid products that contain any added sugars in them, as well as using sugar at home in foods and drinks.

- Prioritise protein, fibre and healthy fats

To help avoid chronically high blood sugar levels, it’s important to base your diet on wholefoods rich in proteins, fibre and healthy fats. Protein can be found in meats, poultry, fish, eggs and pulses and healthy fats in oily fishes, nuts and seeds, coconut (and its oil), extra virgin olive oil and avocado (and its oil). Aiming for 50g of fibre a day is also incredibly important to help balance blood sugar levels. This means eating various types of vegetables throughout the day in your main meals. You can do this by aiming to dedicate half of your plate to a variety of vegetables at lunch and dinner.

Processed, ready-made meals, often contain ingredients that can be detrimental to our health if eaten too often. Hydrogenated oils, sugars and additives feature frequently in packaged foods, which can trigger oxidative stress and can have a negative impact on mitochondrial health. Focus on whole foods and cooking from scratch as much as possible, so that you have control over what’s going into your meals.

The pigments in plants that cause them to have vibrant colours, such as the red in tomatoes, orange in carrots and sweet potatoes and greens in spinach and kale, are rich in antioxidants like polyphenols and flavonoids. These molecules scavenge free radicals from the body’s cells and help mop up any damage left by them. Try to vary your vegetable intake so that you make sure you’re benefitting from a wide variety of antioxidants.

Nutrients and enzymes to support mitochondrial health

Aside from the above dietary changes, there are a few nutrients and enzymes that have been well researched in the context of supporting mitochondrial function.

CoQ10 is an important endogenous antioxidant and enzyme that is produced by the body, which plays an important role in something called the electron transport chain, an important process that occurs in the mitochondria, which triggers the production of ATP or energy in simpler terms. CoQ10 is something that is created inside the body, however, we can get small amounts directly from external sources such as our diet. Foods such as organ meats and oily fish have been shown to contain some CoQ10. In addition, deficiencies in cofactor nutrients such as B2, B3 and vitamin E have been shown to play a role in CoQ10 deficiency, as well as the use of statin medication6.

Carnitine is an amino acid that’s synthesised from dietary sources of lysine and methionine, also amino acids. It is responsible for the transport of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria to be oxidised and used to create ATP. In previous studies, patients with CFS have displayed significantly lower levels of acetyl-L-carnitine, total carnitine, and free carnitine; and those with the lowest levels have shown the worst functional capacity 7. Whilst carnitine deficiency is rare, those on long term restrictive diets, as well as those with poor liver function may have issues synthesising carnitine. Lysine and methionine are widely found in many foods such as meats, poultry, eggs, fish, as well as in nuts and seeds, wholegrains such as oats, brown rice, and finally, in pulses.

Alpha lipoic is an important antioxidant that plays an essential role in supporting mitochondrial enzymes involved in glucose metabolism and energy production. In particular, Alpha lipoic acid has been shown to prevent damage caused to the mitochondria by increased levels of a substance called nitrous oxide (NO) in the body. Whilst NO is essential for blood vessel health, too much of it can be detrimental to our cells. This often occurs in acute inflammation, such as during the initial stages of an infection. Alpha lipoic acid has been shown to effectively restore mitochondrial enzyme activities inhibited by excess NO, which has a consequent positive impact on ATP production8.

Supplementation with these nutrients has been explored in some studies9. However, it is important to work with a nutritional therapist or a nutritionist to make sure you’re taking the right dose and to investigate potential drug-nutrient interactions, for those taking medication. In the meantime, following the above dietary and lifestyle guidelines can have a profound impact on health and mitochondrial function.

Sign up to our mailing list

Receive educational articles and latest information on events, campaigns and research

References

1. Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network — United States, March–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:993-998. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1external icon

3. Moldofsky, H., Patcai, J. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, depression and disordered sleep in chronic post-SARS syndrome; a case-controlled study. BMC Neurol 11, 37 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-11-37

8. Sylvia Hiller, Robert De Kroon, Eric D.Hamlett et al, ‘Alpha-lipoic acid supplementation protects enzymes from damage by nitrosative and oxidative stress’, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – General Subjects, Volume 1860, Issue 1, Part A, January 2016, Pages 36-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.09.001 9. Kristin Filler, Debra Lyon, James Bennett et al, ‘Association of mitochondrial dysfunction and fatigue: A review of the literature’, BBA Clinical, Volume 1, June 2014, Pages 12-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.04.001